|

This tour contains musical excerpts in RealAudio format taken from the Naxos CD

Elgar : Orchestral Works (Naxos 8.554409) and used by courtesy of Naxos Special

Markets. The cello is played by Maria Kliegel, supported by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Michael Halasz. For fuller details of Naxos recordings, visit the

Naxos UK and Naxos USA websites.

Remember! These excerpts remain subject to normal copyright

controls.

|

Imagine if Hamlet began with the Prince alone on stage, delivering the lines,

"To be or not to be ..." - no explanation, no setting of the scene, just one character

thinking out loud, leaving us to make what we will of what he says. Elgar does the

musical equivalent at the opening of the Cello Concerto, placing the listener in the

middle of things from the work's opening bars.This is not the way concertos are

supposed to begin. Generally there is an extended orchestral introduction, after which

the solo instrument makes a carefully stage-managed first appearance. In Dvorak's

Cello Concerto, for example, the opening orchestral section lasts a full three-and-a-half

minutes.

|

Beatrice Harrison with cello,

accompanied by Elgar at the piano

|

|

Elgar begins instead with four insistent chords on

the cello that immediately create a sombre mood. They receive a gentle answer from strings,

clarinets and horns, and then the cello becomes more agitated, in a series of rising notes that

seems to promise some emphatic statement. What we hear is something else: the violas launch

into a subdued lament in 9/8 time that was Elgar's original impetus for

the work. He started the concerto just months after the end of the First World War,

and this great elegiac melody is Elgar's lament for all that the war had cost - millions of

lives, and, with them, a way of life. Gently swaying between a half note and a quarter

note as it winds its way through shifting keys, the theme manages to express both the

numbed serenity of grief and the ache within. This main theme is passed from orchestra

to cello and back again, becoming more anguished with each restatement, until it

finally returns on the cello in the same subdued manner in which we heard it first. This

leads to a more animated second theme in 12/8, which begins as a dialogue between

strings and woodwinds. The first theme is heard again, and the movement ends with

three plucked notes on the cello. With its two simple themes that forego any

substantial development, the movement uses one of music's simplest form - the

three-part structure of a song.

|

| Brinkwells

|

|

The second movement is a brief, pastoral interlude,

perhaps inspired by Brinkwells,

the house overlooking the Sussex downs where Elgar lived much of the

time from 1917 to 1919 and regained the desire to compose. After a brief introduction,

the cello launches into a darting melody that has all the

freedom of birds in flight. The episode is a memory of happier days, whether in Sussex or earlier,

on the Malvern Hills, and its sunshine sets off the darker moods of the other movements.

The third movement's adagio shares the same key, B-flat major, as the andante of the Violin

Concerto, and it breathes the same middle-of-the-night atmosphere. As a young man,

Elgar had been to Leipzig and heard some Schumann, whose work he already knew.

"My ideal!" he wrote to a friend, and, thirty-six years later, Schumannesque echoes

haunt the lovingly-shaped melody of the adagio, where

phrase after phrase follows seamlessly and time seems to stand still.

Until now, the concerto has had little of the musical

dialectic - one musical structure countering another - that occurs in most of Elgar's orchestral

works. But in the fourth movement a musical struggle takes place. If Elgar had captioned his

movements, as many German composers liked to do, he might have described it as "Grief goes

out into the world." The orchestra here is brusque and even swaggering, and the bereaved cello

must make its way in these alien surroundings. The cello tries half-heartedly to join in with the

first theme's assertive mood, then introduces a second

theme and leads the orchestra into digressions of its own. When the first theme returns

on the cellos of the orchestra, it is joined by woodwinds and brass, the trumpets shuddering

aggressively.

Now the cello begins an extended soliloquy that is the concerto's core, just as the cadenza of

the Violin Concerto is the core of that work. First it reprises the movement's first theme in

subdued form, as if its violence has been overcome. Some reconciliation seems about

to occur, but instead, with the orchestra muted, the cello gives full expression to its

grief. The adagio's theme reappears, a moment of consolation, perhaps, and then the

cellist takes up the work's opening chords and makes of them a cry of despair like nothing else in music. The orchestra

returns abruptly and brings the work to a hasty conclusion, in Michael Kennedy's words, "as if too

much had been revealed."

|

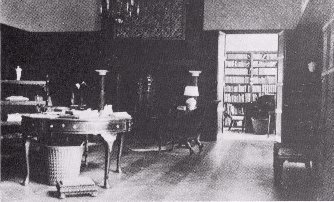

The music room at Severn House,

where Elgar composed much of the concerto

|

|

The concerto is filled with reminders of earlier Elgar. The first theme recalls the 9/8 melody

in one of his first important works, the Serenade for Strings of 1892. The darting

rhythms of the second movement bring echoes of the Introduction and Allegro. And

the spirit of Falstaff can be felt in the finale. Here, however, Elgar employs these

familiar features in a more original and more potent way than ever before - a direction

he would continue in his uncompleted Third Symphony. Anthony Payne's recent

"elaboration" of the sketches for the symphony shows that Elgar was beginning to

pursue this direction further just months before his death in 1934.

Frank Beck

|